by Priya Dialani July 20, 2019

If we ask any celebrity what is the greatest drawback is of being known and you will probably hear some variety in regards to how troublesome it isn’t to have the option to go anyplace without being identified. Regardless (and there are a lot of examples where the two impacts exist), having a famous face implies constantly drawing in the attention of people around you.

Somewhat, we all are superstars in 2019. We’re not all rich and popular, with personal stylists and shouting fans, yet we are known in a manner that would have been outlandish in past decades. Social media urges us to curate our lives, turning notwithstanding something as dull as eating supper into a jealousy rousing story to be “liked” by our “followers.” Almost we all are discoverable utilizing Google, about constantly joined by photographs. What’s more, similarly as it’s hard for Robert Downey Jr. or on the other hand Taylor Swift to stroll down the road without being swarmed, progressively our very own appearances will imply that we have recognized tens, hundreds, or perhaps a huge number of times every day.

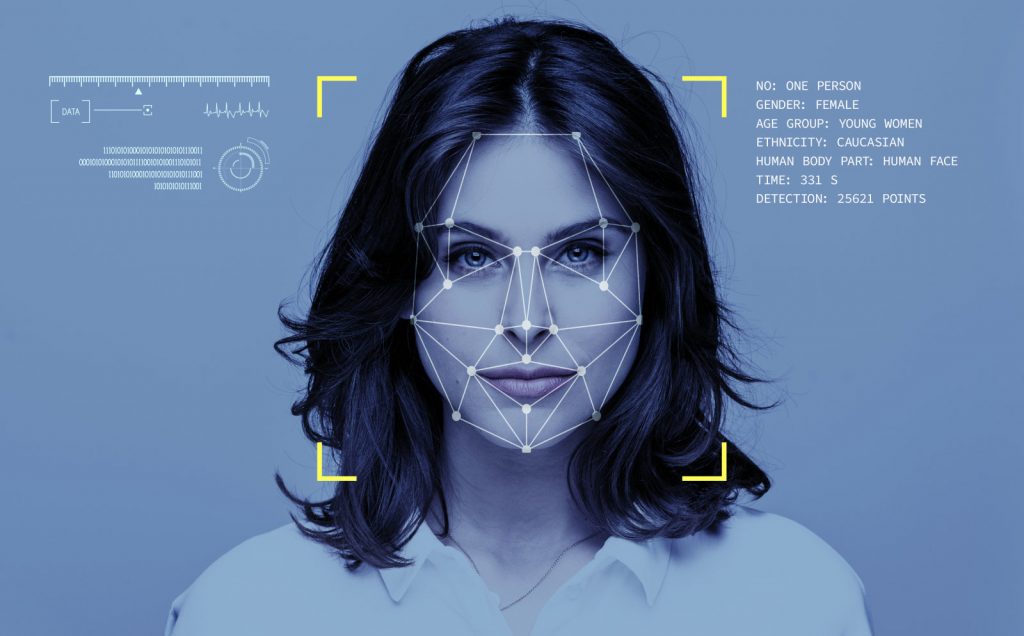

Many databases of individuals’ faces are being accumulated without their knowledge by organizations and analysts, with a considerable amount of pictures at that point being shared around the world over, in what has turned into a vast ecosystem powering the spread of facial recognition technology.

The databases are pulled together with pictures from social networks, photograph sites, dating services like OkCupid and cameras set in cafés and on school quads. While there is no exact check of the datasets, protection activists have pinpointed repositories that were worked by Microsoft, Stanford University and others, with one holding more than 10 million pictures while another had more than 2,000,000.

The face compilations are being driven by the race to make cutting-edge facial recognition frameworks. This innovation figures out how to recognize individuals by breaking down as many digital pictures as could reasonably be expected to utilize “neural networks,” which are complicated numerical systems that require immense amounts of information to create pattern recognition.

Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft (GAFAM) presently consistently publish their hypothetical disclosures in the fields of artificial intelligence, image recognition and face analysis trying to advance our understanding as quickly as could be allowed. The most recent results of tests led in March 2018 and published in May by the US Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate, known as the Biometric Technology Rally, likewise give a phenomenal sign of the best face recognition software available in the market.

Again in 2014, Facebook reported the launch of its DeepFace program which can decide if two captured faces belong to the similar individual, with a precision rate of 97.25%. When stepping through a similar examination, people answer effectively in 97.53% of cases, or simply 0.28% better than the Facebook program.

In June 2015, Google went one better with FaceNet, another recognition system with unparalleled scores: 100% exactness in the reference test Labeled Faces in The Wild, and 95% on the YouTube Faces DB. Utilizing an artificial neural system and another algorithm, the organization from Mountain View has figured out how to interface a face to its owner with practically flawless outcomes. This innovation is consolidated into Google Photos and used to sort pictures and naturally label them dependent on the people recognised. Demonstrating its significance in the biometrics area, it was immediately trailed by the online arrival of an informal open-source version known as OpenFace.

Inquiries concerning the datasets are rising in light of the fact that the technologies that they have empowered are currently being utilized in possibly intrusive ways. Archives released recently uncovered that Immigration and Customs Enforcement authorities utilized facial recognition technology to filter drivers’ photographs to distinguish undocumented outsiders. The F.B.I. additionally has gone through over 10 years utilizing such frameworks to compare driver’s permit and visa photographs against the essences of suspected lawbreakers, as indicated by a Government Accountability Office report a month ago.

There is no oversight of the datasets. Activists and others said they were maddened by the likelihood that individuals’ likeness had been utilized to come up with morally questionable technology and that the pictures could be misused. At any rate one face database made in the United States was shared to an organization in China that has been connected to ethnic profiling of the nation’s minority Uighur Muslims.

In recent weeks, a few organizations and colleges, including Microsoft and Stanford, expelled their face datasets from the web as a result of privacy concerns. However, given that the pictures were at that point so very much circulated, they are probably as yet being utilized in the United States and somewhere else, analysts and activists said.

Facial recognition is controversial. There’s no way to avoid it. Of all the accessible biometric innovations (and there are a lot of them), none convey the same baggage as automated facial recognition. Maybe some portion of it is chronicled. Sometime before, facial recognition enabled us to connect faces with genuine personalities, nineteenth century analysts like the psychiatrist

Hugh Welcher Diamond and the eugenicist Francis Galton portrayed their semi-logical theories on the facial markers for everything from the craziness to guiltiness. These naturally determinist perspectives defended a lot of racist and classist hypotheses in the years that followed.

While an altogether different issue from the inaccuracy of some facial recognition tools today, this crawling undertone of partiality is, for some, individuals, evoked at whatever point we hear, for example, of a protest that a facial recognition framework demonstrates more likely to misclassify minorities than white individuals.

Will a pack of constructive use cases be sufficient to balance human’s worries about mass surveillance innovation? Will the likelihood of turning away another 9/11-style terrorist attack be adequate for individuals to consent to be freely scanned any place they go? As the big-name question of whether an individual is glad to surrender anonymity for the advantages that go with being well known, it’s a tradeoff that will probably vary from individual to individual. While there is an ever-increasing number of applications that are being considered, there is a growing awareness that you are giving away information that could connect you to different records or your social media presence.